How Easy is It to Escape From Prison

Not every inmate thinks about escape. And not every inmate who tries to escape will succeed. So what are the factors of a successful breakout? Forget the hollowed-out Bibles and makeshift shovels. The most important tools are interpersonal—and exist inside the mind.

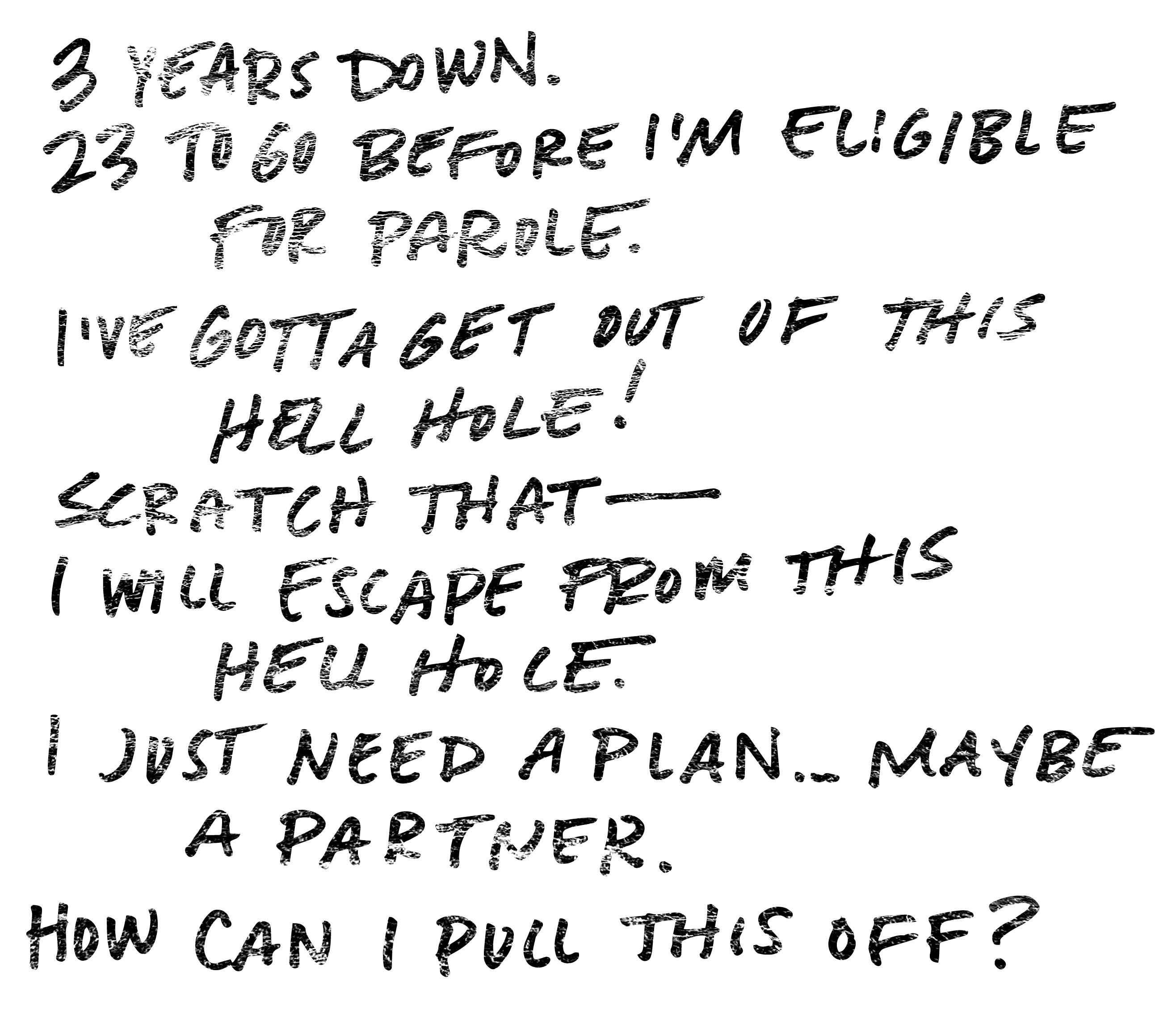

he idea of breaking out of prison usually gestates in the mind of an inmate who is serving a long sentence, who can no longer endure the confinement—who's desperate.

For those who will succeed, breaking out requires more than ingenuity and a prison compound with exploitable weak spots, though. The right mix of psychological tools and a capacity for manipulation are also essential ingredients. In 2015, when Richard Matt plotted an escape from the Clinton Correctional Facility in Dannemora, New York, for instance, he enlisted the help of his fellow inmate David Sweat. Their plan, which Governor Andrew Cuomo called "sophisticated," was also a kind of inside job that involved prison staff. In some ways, relationship-building was the most important element of their escape.

So what do prison relationships, many of which feature survival as a motive and exploitation as a core value, say about human nature behind bars? How can inmates secure an accomplice to help them with their plans? What, in other words, is the psychological playbook behind a prison breakout?

"It's a process, and the ones who succeed in breaking out are very good," says Brent Parker, a retired corrections officer and former associate director of a training academy for prison guards who mingle regularly with inmates. "The planning takes a lot of time, and that's what the inmate has: time."

In addition to Parker, we spoke with Michele Y. Deitch, a renowned prison culture expert, to get inside the minds of those who work and dwell behind prison walls in order to better understand the mental components and interpersonal conditions of a modern-day breakout. This is what they told us:

Credentials

Michele Y. Deitch

Senior Lecturer, University of Texas School of Law

Texas

Harvard Law, Oxford University

Photo by: Brian Birzer

A place where inmates

can befriend employees

According to Deitch, a Harvard Law School graduate and Oxford University graduate in psychology who has studied prison culture and the criminal justice system for 30 years, prisons are a microcosm of society. As a result, inmates and workers typically become acquainted and engage in conversation.

Some prison workers strike up conversations with inmates about their families, for instance, or the routines they have to endure. In some cases, workers can even become the inmates' customers since many prisons have separate economies inside the walls, in which employees can buy prisoner-made goods such as art. "We think of prison guards and inmates as living in different worlds," Deitch says. "There's a saying that prison staffs are doing time but only in eight-hour shifts. The guards are subjected to the same tension, the same boredom."

"Prison staff are often asked to wear an ill-fitting emotional suit of armor that hides some of their best personal qualities."

Because being in a common environment presents the opportunity for small talk, the prisoner-employee interactions can become less rigid over time. And when the employee is not a guard or works in another part of the prison, like the library or the tailor shop, the relationships tend to be even more casual, per Deitch. "There's a real danger in thinking that anytime staff interacts with prisoners that it's for nefarious reasons,'' she says. "Prison staff are often asked to wear an ill-fitting emotional suit of armor that hides some of their best personal qualities. That's unfortunate because that outward facade may prevent them from being able to use their social skills to work with inmates most effectively."

Still, boundaries of appropriate behavior exist. Problems occur, Deitch says, when the relationship drifts outside the bounds of propriety, and the prisoner develops a relationship that persuades the employee to break the institution's rules.

"We call it professional distance—I will be friendly but not over-friendly," Parker says about the kind of relationship guards should maintain with inmates. "As soon as the relationship becomes over-friendly, that's when the staff can get into trouble."

Someone who can

outsmart prison staffers

Being clever, conniving, and patient are all qualities an aspiring escape artist must have. In the annals of famous prison breaks, inmates have made off on rafts constructed from raincoats and rubber cement, have tunneled out with the sharpened end of a spoon handle, and have delayed detection by using pillows and blankets to create the illusion of an occupied cell. The truly brilliant inmate thinks of details that never would occur to prison administrators. For example, Parker tells the story of one inmate who studied the characteristics and mannerisms of a prison guard of the same height so that he could slip into a prison uniform and walk out of the compound unnoticed.

But it's rarely a one-man job, and inmates plotting an escape often seek an accomplice they can trust. "Inmates seek relationships with people who will help them in their mission," Deitch explains. And this is no easy task. "In prisons, it's notoriously tough to trust another person. Prisoners are taught not to trust anyone because other inmates are looking to gain some advantage or obtain some benefits."

So on top of everything else, this inmate has to also be skilled at vetting and choosing the right partner in crime.

An empathetic or

weak employee

An inmate planning an escape or looking for a favor seeks out prison employees who are vulnerable, who show signs of empathy, or who may be plagued with personal problems such as a bad marriage or financial woes.

These scenarios allow for the kinds of conversations between worker and inmate that can create a casual friendship or even a bond. Parker says the strategic-minded convict fishes for any details in that person's life, any interests or passions, by making small talk, which may later evolve into longer conversations. Once a guard and a prison employee share private details about their life, they begin to care about each other to some degree.

"Empathy can arise from feeling sorry for an individual, or that person may be in an unfair predicament," Deitch says.

"It could be something as simple as they learn that they both have kids or they cheer for the same sports team," he says. "The next thing you know, a bond has been formed."

The inmates who are skilled conversationalists will try to develop a rapport with the worker who has sympathy for them, especially if they are serving a long sentence. "Empathy can arise from feeling sorry for an individual, or that person may be in an unfair predicament," Deitch says.

The successful ones who build bonds tend to have the skills of a good salesperson—and, as explained above, they're likely careful listeners, searching for any tidbit of information in a conversation that could ignite or strengthen the friendship. Once the rapport crosses the boundary that separates a professional relationship from a personal one, the prison worker becomes susceptible to manipulation.

Per Parker, "Prisons train staff so that this doesn't happen, but it still happens anyway."

Exploiting

vulnerable employees

Once a bond has been formed, an inmate can manipulate the prison employee, especially when the two are exchanging favors. In a prison romance, the line between convict and prison authority at times can become blurred or suspended because emotions come into play. Inmates can force the vulnerable employees to break prison rules or can persuade them to assist in an escape plan.

"Staff in prisons, like people in the real world, have vulnerabilities," Deitch says. "The prisoner might say to himself, 'If I can become their friend, maybe I can get a candy bar or make them look the other way.' There is a dynamic of mutual exploitation."

By threatening to expose them, inmates can blackmail a prison worker who no longer wants to provide favors or participate in the escape plan. The weak or vulnerable employee will feel pressure to stay the course instead of risking the loss of a job or facing punishment.

"If the relationship goes from a friendship to one of emotional attachment, then the inmate has control and can pull strings to get the staff member to do anything—sex, an introduction to drugs, or an escape," says Parker, who once taught a course to his prison staff about the mind games that inmates play on employees. "The inmate could say, 'I'm going to tell on you, and you're going to lose your job.'"

For an inmate to have any chance of breaking out, he must be completely obsessed with ensuring that all these elements are in place, says Parker. In Escape at Dannemora, a new miniseries presented by Showtime Networks which dramatizes the exploits of Richard Matt and David Sweat, the inmates exhibit exactly the right kind of single-mindedness. Even so, freedom is never a guarantee. "Some of the most manipulative inmates are the most desperate," Parker adds. "They have the most to gain, and the least to lose."

To see how Matt and Sweat crafted a breakout plan by cultivating twisted relationships with prison employees, check out the ESCAPE AT DANNEMORA trailer below and tune-in to SHOWTIME on Sunday, Nov. 18 at 10PM ET.

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/sponsored/showtime-2018/this-is-how-you-break-out-of-prison/2014/

0 Response to "How Easy is It to Escape From Prison"

Post a Comment